- Home

- Tracey Lindberg

Birdie Page 4

Birdie Read online

Page 4

Her strength is surely being tested, she thinks. Her ache for home, home being something she does not yet understand, and a place she has never been, brushes over her like a skirt hem on the floor. If the women could see her insides, she imagines they would see a churning, a quickening, a real live storm inside of her. Whatever was happening, her pulse remains the same while her skin feels lit from within.

The feeling is a little bit like that moment before fainting, if she remembers correctly. She is a bit of an expert and remembers it felt like taking off and then putting on your skin again. She tries to think of herself as a moose stew. She will know when she is done. Her mom made the best moose stew; maybe it was because the meat was always fresh, maybe it was because her bannock was served with it, but that stew was like a tonic that could cure most things. Maybe, she thinks, moose is home.

The last time she had fresh moose was in the fall, before she moved into the city to go to school. She would have been twelve or thirteen. Her mom, of course, made it. Tiny and weary, her mom was unusually heavy on her feet as she got up and walked to the tall pine cupboard that she had recently painted and put in the kitchen. Her short brown arm barely touched the rear of the cupboard and she almost disappeared as she reached for something in the back. Bernice saw her eyes flutter as she grasped what she was looking for and tipped it with her fingers in to get it. She pulled out a brown box, which rattled with change. Her mom seemed to have trouble holding her balance, and she veered a bit towards the stairs trying to make it back to her chair at the table.

Her mom had fished out a five-dollar bill. “Can you go and get me some salt from the HiLo? It’s still early and we’re gonna need some tonight.”

“Salt tonight? We still have lots.” She had lifted the shaker, shaped like a fat dancing white woman. It felt heavy.

“Ayuh, we’ll need more, I’m gonna dry some meat and make some stew tonight.”

“Tonight?” She was trying to get her mom to talk because she didn’t want to go outside in the dark and in the windy cold.

“Don’t stall, put your clothes on. The sooner you get out there the sooner you will get home.”

Bernice had trudged to the front door and put on her jacket.

“Not that one, the parka, and you’d better put your snow pants on, too.”

“I’ll look stupid, I hate those pants, Mom, they’re too small and they make me look …” – she searched for a word – “… like a bimbo.”

Bimbo the Birthday Clown was on every Saturday at 6:30 in the morning during the Uncle Bobby show. He was the worst part of the Professor Kitzel, Max the Mouse and Spider-Man marathon that she, Freda and whichever cousins were over used to watch together.

“Don’t use that word in this house,” her mother spat venomously at her. “Don’t you ever use that word.”

Though tiny, she solidly planted herself in front of Bernice, and assumed a threatening stance. For a second she was afraid her mom would smack her.

“Don’t hit me.” Bernice cowered in the corner, fully dressed and hopefully padded enough with her coat, snow pants and mitts not to feel the blow too hard.

Something had registered on her mom’s face. Something at once shocked and ashamed. She stepped back and said quietly, “Get out, Birdie, go for a walk and get some air. You spend too much time indoors. Go now.”

In the stillness of her room, Bernice hears her own breath, a bit ragged. She can feel her mom’s resignation to something but doesn’t want to know what it is. Above the rumble of the noise from the bakery, she barely registers and refuses to recognize something from her mother that is at once familiar and painful. Her palate for pain, though, is well developed. She recognizes the flavour in her mouth as bitter and dull. It tastes like defeat.

Bernice had put on a toque and stepped into the early evening dark of the near-winter. The wind wheezed and whistled at her as she trudged through the new snow. It was hard and starting to get packed beneath her feet, and she thought that it was starting to get that brown sugar feel. She walked as quickly as her asthma and padding would allow her. She crossed the main road only when all of the traffic had passed, and when she started to move again she felt a chill in her legs that served as notice that she had been standing on the roadside for a very long time.

She slipped and almost fell on the icy lot of the HiLo Mart.

“Nice move, buffalo,” a voice called out.

It was Tim Lerat, dressed in a jean jacket and hunting cap. He looked even spookier at night with his hair unkempt and a cigarette dangling from his lips. He was, of course, with a group of younger boys who tried to look and act like him whenever possible.

“Yeah, way to go,” echoed Shorty Moostoos. He was fifteen, two years younger than Tim, but he was just a bit taller than Bernice.

“Get bent,” she yelled at them as she reached the door, silently thanking Mickey Spillane for the comeback.

She watched them warily through the glass of the HiLo, but only when she turned corners and stopped to stare at goods on the shelves. They were waiting for her like the wolves in Call of the Wild. She imagined them scratching at the glass, the hard nails of animals clicking against glass as they frantically tried to scratch through to their prey.

She looks at Old Man Pocock, he watched her every move, the owner of the HiLo trusted no one. But Bernice knew all about him. He suspected that everyone did what he had been doing for years, trying to make the best of his situation by ripping off the old, imbecilic and immature. Surrounded in his wealth, he wanted more and couldn’t see what he had. He was like the men in The Little Prince who could not see a single rose in their flower gardens because they were always looking for more. She was certain he saw only a hat, and smiled because she could not only see the elephant that lived within the snake, she could hear it call to her.

“What are you looking for, Bernice Meetoos?” He yelled at her from a table-length away.

She glanced at the door; the wolves were still there, spitting and smoking as all bad wolves do.

“I’m, uh, looking for, uh, some salt.” She knew she was standing right in front of the boxed Sifto.

“Are you blind? It’s right there.” He lurched off his stool and pointed to, but did not touch, the salt. It was almost like he didn’t want to touch something that she was about to buy and take home.

“Oh, thanks, yeah, I see it.”

She lifted it off the shelf and dropped it immediately, the sound of Shorty’s laughter as Tim howls startling her. She looked towards the door and sees that Tim had taken his pants off, no – had pulled them down, to reveal his bottom, cleaved, spread and pressed against the glass directly in front of her.

She stared at this display in wonder. She was quite sure he had hair on his bum.

She looked at Old Man Pocock and pretended she didn’t see what he knew she saw. Walking to the till, she pulled off her mitten and took out the five-dollar bill. She passed it to him and watched him carefully as he counted out her change with the three fingers he had on his right hand. She waited for him to put the change on the counter, but as usual, he stood there until she put her hand out to receive the change. He has stopped trying to shortchange her as her math skills have caught him twice before. Freda told her that the old man does it for fun, to separate the smart kids from the dumb ones. Bernice didn’t care and never lingered in the store.

“I’d like a bag, please.”

He grunted and reached under the counter; he had never offered her a bag in her whole life.

She turned slowly on her heel and was relieved to find that the wolves had disappeared. She knew that they wouldn’t be far away, though, and she ran the three blocks home. When she reached the corner of her street she was wheezing and puffing, her breath was shallow and it came from her throat. She slowed down and tried to do her deep-breathing exercises.

By the time she reached her house her breathing was almost normal. There were vehicles parked in the driveway and in front of the house. She wal

ked to her uncle Larry’s truck, as it seemed to be in the centre of the driveway. Sometimes he had cases of beer in the back of his truck. She thought that she would hide them if he did. She had done this before, and on two of the occasions the party broke up early. She looked in the window of his Chevy and saw Terry’s purse spilled on the seat. She can tell that it was hers because the leather was bright green. It must have come from a cow something like the horses in The Wizard of Oz at the Emerald City, she thought.

She looked in the back of the truck and found not beer, but blood. It looked like a pink Slushie, the blood in the truck box crystalline and frozen. There were pink drops and red blotches leading over the open end of the box and up the driveway. She followed them to the garage door. Nancy Drew would know what to do, but all she could think to do was to climb up the snow piled on the side of the garage between her house and the Olsons’ and peek in the window.

The party was now a post-hunt party. Terry, her uncle Larry, her dad, Colin Ratt, Leonard Auger and Billy Morin sat on milk crates around an inky black moose. She saw that the beer had made it into the garage and that the men were flushed and talking with lots of gestures and movement. Terry laughed and tipped her head back at something her dad whispered to her. She went to grab a beer and bent over right in front of her dad.

“Bimbo.” She breathed onto the small glass pane, fogging it up instantly. The frost covered Terry’s miniskirted legs.

There was plastic on her dad’s workshop tables, which had been pushed together, and there was a big roll of brown butcher’s paper on the cement floor.

The men, as if receiving a signal, moved towards the moose. The garage tilted and blurred towards her as she saw the flashing of a knife in her uncle’s hand. He skinned the moose cleanly and quickly, leaving the nose. The nose is a delicacy, she knew, and they would have it at feast. Steam rose off the still warm moose as cold air hits its nakedness. Terry grabbed a knife, like a prisoner on a prison break, and grabbed the moose’s ear. The blood clouds Bernice’s eyes and she retched, missing herself and hitting the lilac shrub. She sat down and watched the brown Cokey liquid freeze to the sparse bare branches of the tree like tiny ornaments on a Christmas tree.

Sometime later, she heard her mom calling her name and after that she felt her arms around her.

“Come inside, my girl, you’ve been gone so long.” She peeked in the window. “They enjoy this more than they should.” Her voice sounded funny and as she clung to her mother, she thought she saw tears sparkling in her tired liquid brown eyes.

Bernice was put in a hot bath, her mom squeezed oranges into it.

Bernice kept adding hot water until the heater was empty. She pulled on her mom’s Sturgeon Lake T-shirt and crawled into her own bed. Her mom had put an extra blanket on the bed and came in every once in a while to see if Bernice was asleep yet. She was achy and thought she might be sick, but she was too tired to talk.

Later, the sounds of heavy boots walking in the front door and pounding across the floor, to the freezer, she imagined, woke her up.

And later still, the clank of beer bottles being placed on the floor and the thump of boots removed as the party moves from the garage to the next house. She looked at the little clock her mom gave her for Christmas. It was four-thirty.

There was the sound of hushed talking and then louder arguing and she faintly heard her mom speaking harshly to her husband and then her brother. There was yelling and then some scuffling. Bernice was not sure how long this went on for, as she dozed, but she was awakened by the sound of the beer bottles clinking and a door slamming. Later, she woke and heard nothing, assumed everyone had passed out, and felt herself grow less nervous.

Ahhhhhhh. She misses her mom. The ache in her stomach grows and reaches her chest. Soon it will spill into her throat and well up in her eyes if she is not careful. That love, that love that runs through her veins rushing like a stream threatening to spill onto the flood plain was rich and thick. The memory stills her and her breathing, quite unnoticed, stops.

She can smell the dark in the room, hear the sounds of emptiness, and Bernice feels Freda’s small body move onto the mattress. How long has she been … travelling? She keeps her eyes closed but thinks she feels her cousin’s eyes on her. That lasts a long time.

She feels Freda’s agitation next to her as her cousin flips over, the old floor in Bernice’s apartment barely sighing as if the movement punctuates a sentence filled with tired verbs and exhausted pronouns.

She wonders if Freda can even see her anymore, or if there is an empty space in the bed where she used to settle.

I’m not here, she thinks. I’ve changed.

4

WHERE SHE IS

kasakes: a glutton, one who eats a lot

pawatamowin

She dreamsmells almonds and pesto.

THE SMELL IN THE LITTLE BAKERY is yeasty and rich and chases the aroma from her head. Lola must have made dinner buns in the night, Bernice thinks to herself. That was her job before … before she took to her bed. With a sick headache, she thinks, opening her eyes. And, while she doesn’t miss getting up at four to bake, she realizes she has begun to miss the steady stream of chatter around her that customers brought into Lola’s with them. She would rarely wait on anyone but was always pleased when someone was kind to her. Her legs ache a bit, like she has been sleeping outside or walking all night. In that continuum that now exists between her body (which she has come to think of as a shell) and her spirit (within which emotions, thoughts and memories layer over each other, tendrils of fog on a road), she recognizes that her body is emotively moving. Anyone watching her would think she was in the throes of a deep sleep and suffering from restless leg syndrome. In the tendrils, Bernice realizes there is remorse in her body and she is trying to kick it out. Her shell rejects remorse. Shame. Feeling bad over feeling good.

When she first arrived at Gibsons she behaved … well, she did not behave. Some mornings she awoke lying alone in her room. Some mornings she sat up with a start, realizing she was in some strange place with some strange person next to her. One morning she awoke next to a stinky man. There was something entirely unpleasant about the person in bed next to her. He had a military haircut – and god – he couldn’t have been an active serviceman for some twenty years. It was a brush cut, salt-and-pepper hair splayed straight up and out for the world to see. He was no Jesse. He was not even Nick Adonodis. He rolled over, farted, and she stiffened, bracing herself for the unpleasant feel of his touch or growl of his talk. The stench was unaccompanied and therefore welcomed.

She knows she shouldn’t have gone to the motel with him. There are a lot of shouldn’t haves. Drunk gin. Flirted. Talked to strangers. Drunk gin. Flirted with strangers who bought her gin. It really was a limited and vicious circle. The first drink was the hardest. Well, getting to the first drink was the hardest. She didn’t allow herself the luxury of just one drink (or just one anything, for that matter). Getting over the guilt of being a dry drunk/drinker (because, let’s face it, she was never going to admit it) cost the most. Beyond that, though, when the world turned rosy and her armour gelatinous it got easier and easier.

She drank. She drank and the lines between her and other people blurred. She could hug, express love, laugh at things that her sober self would not allow her, and dropped thinking for feeling. She drank to feel something like she feels now, wrapped in the mink blanket Freda has brought, peaceful in her wakesleep, and able to feel her past without experiencing it – able to see it without reliving it.

That helps, because some of it was really quite – humiliating? No. She refuses it, feeling her hands tighten on their own. Humbling. It felt to her like she had slept in that cheap hotel with that married man about a hundred times. Not really, but the feeling of that particular model of man would not leave her easily. Art? Al? She remembers his name had only one syllable – about all she could manage by midnight. Come to think of it, maybe that was why she went home with him, instead

of his two-syllabled friend. His last name was one of the Christmas reindeers. Well, it really doesn’t matter anyhow, she supposed.

It was clear to her from the start that this was no ordinary guy. A skinny white dishevelled man hanging out at an Indian bar (how come they all have imperial names, she wonders: King George, The Empire Hotel, The Lord Tupper, The Royal?) was not such an odd thing. That he was somewhat attractive and well dressed was something of an oddity. But, when she looked into those eyes, those blue eyes (what colour were Knud Rasmussen’s eyes?), she saw that something was amiss. What it was became clear soon enough, but at the time it just looked like near-crazy. Quasi-nuts. Pseudo-maniacal.

And while he was generically white-guy attractive, she had never been that attracted to generic. Or white guy. Or attractive guys. He honed in on her the moment he saw her. Then: she thought it was her spirit. Now: she knows it was blood in the bar water that drew him like a shark. Before she sank, back when she was willing to sleep with Art/Als, during the time of the shark, she didn’t know that you couldn’t really bury your pain and fear. And. While they were not the largest part of her, they rose to the surface like soured cream in coffee.

In the discord that floats through bad barrooms thicker than cigarette smoke and which runs faster than the beer on tap, her radar for mean was off.

That morning. The morning of Art/Al? she was a particular mess. Her shift at Lola’s was starting in twenty minutes. Time enough to wash him off and out of her and get to the bakery. If she ran. Which she didn’t. Opting to go unnoticed, she did the sneak. Pulled him close and flipped over – no small task for her two-hundred-plus-pound frame. He growled in his sleep (she seemed to recall that he growled in his wakened state as well). Taking care not to tip over the gin bottle, she had pulled on her 3X panties, 2X denim skirt and size 5 shoes. Picked up her purse, the gin bottle and his wallet. And left Art/Al to his humming, farting and snoring.

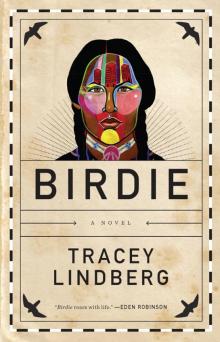

Birdie

Birdie